Protein myths debunked

FACT: Vegetables have plenty of protein, and they're complete proteins as well

by Michael Bluejay • Last update: May 2023

| Protein content of various foods | |||||

| 6.7% |

|

||||

| 11% |

|

||||

| 13% |

|

||||

| 22% |

|

||||

| 28% |

|

||||

|

2.5% 11% |

|

||||

|

Protein given as a percentage of calories. Food figures are

averages for several foods in each category5 and

were taken from the bible of nutrient data, the USDA

food database. Human need is from peer-reviewed

research2, US govt. recommendations3,

and WHO4 Chart from MichaelBluejay.com |

|||||

Common vegetables have much more protein than you need, and contrary to popular myth, they're complete proteins as well.1 Whoever told you otherwise didn't bother to look up the actual numbers. So let's see at what the science actually says about this.

We need only 2.5 to 11% of our calories as protein, according to peer-reviewed research and the official recommendations.2,3,4 That amount is easily supplied by common vegetables.5 Vegetables average around 22% protein by calorie, beans 28%, and grains 13%,5 as shown in the chart.

The U.S. government's recommendation is 5-11%, based on various factors.3 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a similar amount.4 And these recommendations are padded with generous safety margins, to cover people who need more protein than average. The National Institutes of Health and WHO's recs are intended to cover 97-98% of the population. That means the overwhelming majority of people need less than the official recs, even though the official recs are still easily supplied with plant foods. The median person needs only 80% of the official rec.4

In any event, whether you think our needs are closer to 2.5% or 11%, you can see from the chart that it's nearly impossible to fail to get enough protein, provided that you make sure to eat food. Every single whole plant food has more than 2.5% protein, and every group averages at least 11% except for fruit. Protein is one of the easiest nutrients to get.

The figures for food are from the bible of nutrition data, the USDA FoodData Central database.5 The science is exceptionally clear, for anyone willing to look. (Unfortunately, many doctors and dietitians haven't looked.)

So plant foods easily supply our protein needs. The

truth is that if you're eating food, you're eating protein—and

almost certainly more than enough.

It's meaningless to talk about a "source of protein", since all whole foods have plentiful protein. In other words, every whole food is a "source of protein". You don't have to eat certain, special foods to get protein. You just have to eat any whole food. That's it.

This isn't just theoretical, either. A massive review of 64 studies over twenty years concluded that "protein intake...in people following plant-based diets [was] well within recommended intake levels." Vegan diets averaged 13% protein (about double the typical need), compared to 16% for meat-eaters. (Nutrients 2022) So, that's what the science says. It's probably not what you'll hear from your doctor or dietitian because, again, many health professionals haven't looked up what the science actually says.

Of course, many health professionals have looked up

the science, and those who do say the same things you're reading

in this article. Take Marion Nestle, Ph.D, chair of the

Department of Nutrition at New York University:

"We never talk about protein anymore, because it's absolutely not an issue, even among children. If anything, we talk about the dangers of high-protein diets. Getting enough is simply a matter of getting enough calories."9

Calorie & Protein Calculator

| Daily Needs |

|

| Energy (calories) | Protein |

Protein of vegetables:

| 50% | Spinach | 22% | Green Beans | 12% | Onions | |

| 33% | Cauliflower | 21% | Bell Peppers | 11% | Potatoes | |

| 31% | Mushrooms | 20% | Tomatoes | 13% | Corn | |

| 30% | Zucchini | 17% | Cucumbers | 10% | Eggplant | |

| 29% | Peas | 17% | Celery | 9% | Sweet Potatoes | |

| 27% | Broccoli | 15% | Beets | 9% | Carrots | |

| 26% | Lettuce, iceberg |

It's true that meat has more protein than vegetables, but the

amount in vegetables is already much more than you need. The

extra protein in meat isn't better, it's useless. If you're

shopping for a car and one goes 200 miles an hour and the other goes

300, it doesn't matter, since the maximum speed limit anywhere in

the U.S. is 85 mph. Two hundred mph is more than enough for a

car, and 22% protein from vegetables is more than enough when your

protein needs are only 2.5 to 11%.

Oh, but you've heard that plant protein is "incomplete", right? Well, that's not true either. Let's have a look....

Vegetables are complete proteins

We've all heard that plant protein is "incomplete" compared to meat protein, and that plant foods have to be carefully combined to make a "complete" protein. But that's an urban legend that was never based on science. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) abandoned that idea decades ago. Susan Havala Hobbs, Ph.D, R.D. describes how the AND discarded the protein combining myth:

There was no basis for [protein combining] that I could see.... I began calling around and talking to people and asking them what the justification was for saying that you had to complement proteins, and there was none. And what I got instead was some interesting insight from people who were knowledgeable and actually felt that there was probably no need to complement proteins. So we went ahead and made that change in the paper. [The paper was approved by peer review and by a delegation vote before becoming official.] And it was a couple of years after that that Vernon Young and Peter Pellet published their paper that became the definitive contemporary guide to protein metabolism in humans. And it also confirmed that complementing proteins at meals was totally unnecessary.16

There's a very easy way to see the completeness of plant proteins, that almost no nutrition writers have bothered to do: Look at what's actually in the food! It's not like this is a secret; that data has been publicly available from the USDA for decades, and now the USDA's database is even online.5 Below is what it looks like when you actually look up the numbers.

Vegetables are complete proteins |

|||||||||

| Amino acid >> |

Isoleu- cine |

Leucine |

|

+Tyrosine |

|

|

|

|

|

| Human Need |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Brown Rice | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tomatoes | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Potatoes | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Green Peppers | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Corn | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lettuce (iceberg) | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Celery | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cucumbers | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Oats | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Carrots | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Broccoli | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pinto Beans | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Amino

acid need from the World Health Organization4, food

composition from the USDA nutrient database5.

Analysis is for each individual food all supplying calorie needs

(closest to the "low active" category for a 5'11" 181lb. 25BMI male,

as per the FDA).3

So when we compare the actual requirements to what plant

foods actually contain, we find that basic plant foods

aren't incomplete at all. They have every essential

amino acid, in excess of what we need. It might not surprise

you that beans are a complete protein by themselves, but even

carrots are a complete protein. Tomatoes are a complete

protein. Celery is a complete protein. Even iceberg

lettuce is a complete protein.

(Those who would object that we can't eat enough lettuce to satisfy our protein needs are wildly missing the point. The point of using a day's worth of calories for a single food is simply to show mathematically how the food measures up, not to suggest that anyone could or should eat only a single food. These plant foods are complete no matter how much or how little of them you eat. That is, if only 1% of your diet is lettuce, then lettuce supplies more than 1% of your protein and amino acid requirements.)

A 2015 study analyzed the dietary intake and blood amino acid

levels of various groups, and found that vegans met the RDA

for each and every amino acid. (Jack

Norris, R.D.)

Interestingly, the amounts for "Need" in the table are twice what they were until recently. The original recommendations in the WHO's 1973 and 1985 reports were based on William Rose's pioneering work in the 1950's, and were considerably lower.13 Rose determined the levels needed by his subjects by intentionally feeding them diets with a synthetic mixture of declining levels of amino acids until they became deficient. After finding the highest amount needed by any subject, he then doubled that figure to arrive at his recommendation.14 And the current WHO recommendations have doubled their earlier figures again. And even with all these increases, individual plants still measure up as fully complete.

Experts confirm that plant proteins are complete

Besides the AND, other medical and nutrition professionals who have actually looked at the science know that there's no need to carefully combine proteins. For example:

Dennis Gordon, M.Ed, R.D.:

[C]omplementing proteins is not necessary with vegetable proteins. The myth that vegetable source proteins need to be complemented is similar to the myths that persist about sugar making one's blood glucose go up faster than starch does. These myths have great staying power despite their being no evidence to support them and plenty to refute them.15

Jeff Novick, M.S., R.D.:

Recently, I was teaching a nutrition class and describing the adequacy of plant-based diets to meet human nutritional needs. A woman raised her hand and stated, "I've read that because plant foods don't contain all the essential amino acids that humans need, to be healthy we must either eat animal protein or combine certain plant foods with others in order to ensure that we get complete proteins."I was a little surprised to hear this, since this is one of the oldest myths related to vegetarianism and was disproved long ago. When I pointed this out, the woman identified herself as a medical resident and stated that her current textbook in human physiology states this and that in her classes, her professors have emphasized this point.

I was shocked. If myths like this not only abound in the general population, but also in the medical community, how can anyone ever learn how to eat healthfully? It is important to correct this misinformation because many people are afraid to follow healthful, plant-based, and/or total vegetarian (vegan) diets because they worry about "incomplete proteins" from plant sources. ...[I]f you calculate the amount of each essential amino acid provided by unprocessed plant foods...you will find that any single one...of these whole natural plant foods provides all of the essential amino acids....

Modern researchers know that it is virtually impossible to design a calorie-sufficient diet based on unprocessed whole natural plant foods that is deficient in any of the amino acids. (The only possible exception could be a diet based solely on fruit.)17

John A. McDougall, M.D.:

Many people believe than animal foods contain protein that is superior in quality to the protein found in plants. This is a misconception dating back to 1914, when Osborn and Mendel studied the protein requirements of laboratory rats.[11]... Based on these early rat experiments the amino acid pattern found in animal products was declared to be the standard by which to compare the amino acid pattern of vegetable foods. According to this concept, wheat and rice were declared deficient in lysine, and corn was deficient in tryptophan. It has since been shown that the initial premise that animal products supplied the most ideal protein pattern for humans, as it did for rats, was incorrect.... It is clear that even single vegetable foods contain more than enough of all amino acids essential for humans.... Furthermore, many investigators have found no improvement by mixing plant foods or supplementing them with amino acid mixtures to make the combined amino acid pattern look more like that of flesh, milk, or eggs.[35-44]... Nature has designed vegetable foods to be complete. If people living before the age of modern dietetics had had to worry about achieving the correct protein combinations in their diets, our species would not have survived for these millions of years.10 A careful look at the founding scientific research and some simple math prove it is impossible to design an amino acid–deficient diet based on the amounts of unprocessed starches and vegetables sufficient to meet the calorie needs of humans. Furthermore, mixing foods to make a complementary amino acid composition is unnecessary.34

Andrew Weil, M.D.:

You may have heard that vegetable sources of protein are "incomplete" and become "complete" only when correctly combined. Research has discredited that notion so you don't have to worry that you won't get enough usable protein if you don't put together some magical combination of foods at each meal.18

Charles Attwood, M.D.:

Beans, however, are rich sources of all essential amino acids. The old ideas about the necessity of carefully combining vegetables at every meal to ensure the supply of essential amino acids has been totally refuted.19

The original source of the protein combining myth recants!

Interestingly, it's very easy to trace the protein combining myth to its original source: A bestselling book called Diet for a Small Planet, in 1971. The author, Frances Moore-Lappé, wanted to promote meatless eating because meat production wastes horrific amounts of resources. But she knew her readers would think you couldn't get enough protein from a vegetarian diet, so she set out to reassure them, by telling them that if they carefully combined various plant foods, like rice and beans, the supposedly inferior plant proteins would become just as "complete" as the ones in meat.

Lappé got her idea from

studies that were done over 100 years ago, on rats. The

researchers found that rats grew best when the proteins in their

diets were in the same proportions as found in animal foods.

From this finding, animal proteins were arbitrarily labeled

first-class while plant proteins were deemed inferior. The

problem with this conclusion is that rats are not simply smaller

versions of people. Baby rats actually need a higher

percentage of protein than do baby humans, because they grow a lot

faster. Humans grow slowly. It takes a human baby half a

year to double its birth weight. A rat does it in only

four and a half days.11 So clearly rats are

going to need more protein. In fact, rat milk is a whopping

49% protein12—much higher than the mere 6% found in human

mother's milk.

Lappé got her idea from

studies that were done over 100 years ago, on rats. The

researchers found that rats grew best when the proteins in their

diets were in the same proportions as found in animal foods.

From this finding, animal proteins were arbitrarily labeled

first-class while plant proteins were deemed inferior. The

problem with this conclusion is that rats are not simply smaller

versions of people. Baby rats actually need a higher

percentage of protein than do baby humans, because they grow a lot

faster. Humans grow slowly. It takes a human baby half a

year to double its birth weight. A rat does it in only

four and a half days.11 So clearly rats are

going to need more protein. In fact, rat milk is a whopping

49% protein12—much higher than the mere 6% found in human

mother's milk.

Lappé's idea of protein combining spread like wildfire. Soon the National Research Council and the AND, without bothering to verify the hypothesis, jumped on the bandwagon by saying that plant proteins were inferior and had to be combined.10

But it wasn't long before Lappé realized her mistake, and owned up to it. In the 1981 edition of Diet for a Small Planet, she recanted:

In 1971 I stressed protein complementarity because I assumed that the only way to get enough protein...was to create a protein as usable by the body as animal protein. In combating the myth that meat is the only way to get high-quality protein, I reinforced another myth. I gave the impression that in order to get enough protein without meat, considerable care was needed in choosing foods. Actually, it is much easier than I thought.With three important exceptions, there is little danger of protein deficiency in a plant food diet. The exceptions are diets very heavily dependent on [1] fruit or on [2] some tubers, such as sweet potatoes or cassava, or on [3] junk food (refined flours, sugars, and fat). Fortunately, relatively few people in the world try to survive on diets in which these foods are virtually the sole source of calories. In all other diets, if people are getting enough calories, they are virtually certain of getting enough protein."20[emphasis in original]

It says a lot about Moore-Lappé's integrity that she owned up to the very mistake that made her a household name. (It's also worth noting that her book pretty much single-handedly jump-started the vegetarian movement in the U.S. in the 1970s.)

In any event, if you came to this page with the idea in your head that plant proteins have to be combined, I hope it means something to you that the person responsible for that idea being in your head in the first place said that she was wrong.

What's truly ironic is that everyone

who has the mistaken idea about protein combining got it from

Moore-Lappé, directly or indirectly, but she took

it back.

What's really crazy is how many people cling to the

protein-combining myth even after learning that the very source of

that myth admitted that it's not true. If people

believed her when she made the original claim, then why won't they

believe her when she said her claim was wrong?

Digestibility is not a problem

Some critics have screamed at me that plant protein isn't digested

as well as animal protein. Well, say it, don't spray it.

Once again, these critics haven't bothered to look up the numbers.

The protein in beef and fish in 94% digestible. That's

actually less than the digestibility than plant foods like white

flour (96%) and peanut butter (95%). Peas, rice, whole corn,

soy flour, oatmeal, and whole wheat flour aren't far behind

(86-88%). Beans, despite their high protein content,

are a bit further down on the digestibility scale (78%).3

(By the way, the WHO report didn't list other vegetables, or I would

have listed them here.)

This shows that digestibility isn't a problem at all, in

practical terms. Plant foods still provide more than

enough protein, even after considering lower digestibility.

From the numbers above, the protein in meat is digested 20.5% better

than that of beans. If we take someone with a higher than

average need for protein (10% of calories), and add 20.5% to that

figure to account for lower digestibility, they now need 12.5%

protein instead of 10%. And again, grains average 13% protein

and vegetables average 22%—far more than enough.

Protein quality is not a problem

Some critics have pointed to various measures of protein

quality, such as PDCAAS, which say that plant protein is inferior.

Such critics are missing the obvious: The quality measures are

mostly based on the amounts of amino acids in foods,21

and I've already explained in detail, with a nice chart, using

numbers from official sources, that vegetables absolutely contain as

much or more than you need of each individual amino acid. That

is, plant foods provide more than enough protein even after you

account for any differences in digestion or protein quality.

Your body doesn't care whether the protein quality of what you're

eating is "very high" vs. simply "high". It's concerned only

that you eat enough. As long as your body is getting as much

protein as it actually needs, it doesn't matter what form the

protein comes in.

Critics are confusing more with better.

Yes,

animal foods have more protein, but that's not a

benefit. There's absolutely no advantage to eating way more

protein than your body can use. If you need 2500 calories a

day, would you be healthier with 3000 calories a day?

No. In fact, eating that much more than you need would be

detrimental to your health. The same is true of eating too

much protein. Excess protein intake has been linked to bone

loss, osteoporosis, kidney damage, kidney stones, immune

dysfunction, arthritis, cancer promotion, low-energy, and overall

poor health.22 The science on this is very clear.

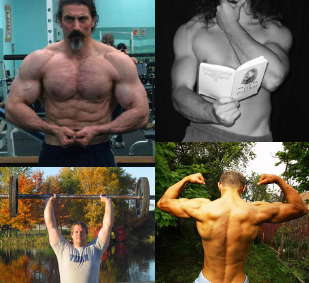

Vegan diets supply plenty of protein for building muscle

Vegan bodybuilders shatter the myth that vegans are skinny and malnourished. (Pictured: Avi Lehyani, anonymous, Ryan Wilson, Robert Cheeke)

Plant foods supply plenty of protein even for athletes and those trying to build muscle. In a study of older adults doing either lower-body or whole-body resistance training increased their muscle strength and mass on the US RDA for protein of only 0.36 g per lb. of body weight.25 For a 120-lb. person eating 2000 calories or a 180-lb. person eating 2500 calories, that's 8.6% to 10.4% of their diets as protein. And remember, vegetables average 22% protein and beans 28%.

Another study suggested that established bodybuilders need around 0.48 g of protein per pound of body weight per day (1.05 g/kg).26 (Incidentally, it also found that bodybuilders required 1.12 times and endurance athletes required 1.67 times more daily protein than sedentary controls.) For an 180-lb. athlete the 0.48 g/lb. figure is 90 grams (360 calories from protein). For a 3000-calorie diet, that's 12% of calories from protein. And again, vegetables average 22% and beans 28%.

Those starting a muscle-building program may need more protein, 0.77 g/lb. (1.7 g/kg).27 For a 180-lb. athlete that's 139 grams (556 calories). On a 3000-calorie diet, that's 18.5%, still less than supplied by common vegetables.

If the athlete eats more than 3000 calories a day, or weighs less than 180 lbs., then the percentage of protein required goes down even more.

In 2009 three major health organizations endorsed the 0.5 to 0.8 g/lb. (1.2-1.7 g/kg) figures above (American Dietetic Association, Dietitians of Canada and the American College of Sports Medicine)28

More is not better. As one paper said, "Ingesting more protein than necessary to maintain protein balance during training (e.g., >1.8 g/kg/d) does not promote greater gains in strength or fat-free mass."29. One study of 60 elderly men doing power training showed that supplementing with whey or casein didn't lead to muscle improvement versus no supplementation.32

Jack Norris, RD points out that nutrient recommendations are always "padded" with safety margins. That is, most people need less:

Considering the information reviewed above...it seems reasonable to conclude that the protein needs of most vegan bodybuilders are somewhere between 0.8 and 1.5 g/kg (0.36 and 0.68 g/lb) of body weight....The Food and Nutrition Board, which sets the RDA, reviewed Lemon et al.'s study and others and concluded there is no sufficient evidence to support that resistance training increases the protein RDA of 0.80 g/kg [0.36 g/lb] for healthy adults.30

For more on protein and muscle-building, see my separate article

on Protein & Strength.

Is it possible to be protein deficient?

Experts know (and have said) that it's essentially impossible to design a diet based on whole foods that's deficient in protein. But there are two cases where it's possible to be deficient.

The first is a diet that's not based on whole foods, meaning lots of processed foods. Foods (or drinks) with lots of fat or sugar have lots of calories but less protein. This doesn't mean that every diet that includes processed foods is protein-deficient, but it's possible. It's much more likely that a diet high in processed foods would be deficient in other nutrients.

The second is a diet that doesn't provide enough calories could be protein-deficient, but not necessarily. For example, if someone reduced their calories by a whopping 20%, they'd need 25% more protein as a percentage of calories.33 Though if someone normally needing 8% protein cut their calories and needed 25% more, then they'd need 10% protein, which is still less than the 13% in grains, 22% in vegetables, etc.

Other objections

I get lots of misinformed objections to this article, but some

of it is really wacky. One particular objection is that

my use of recommendations from the World Health Organization (WHO)

is wrong, because the WHO's recommendations are supposedly designed

only to prevent extreme malnourishment among impoverished

third-world residents. Such critics have apparently never

actually read a WHO report, since such reports say the exact

opposite. For example:

- "The levels of energy intake recommended by this expert consultation are based on estimates of requirements of healthy, well-nourished individuals."31 (emphasis in original)

- "[T]he objective of this report is to make recommendations for healthy, well-nourished populations..."31

It's really meat that's incomplete

It's kind of silly to single out protein, just one of the many nutrients, just so we can declare plant proteins to be incomplete (although they're not). Why aren't we declaring meat to be an incomplete vitamin? Because it is, you know. For example, beef is completely devoid of Vitamin C, an essential nutrient without which you'd die. And beef doesn't just have a lower level of this essential nutrient, it has zero. So why didn't the authorities ever caution us that we need to combine various foods to get a complete vitamin?

But actually, no combination of meat will make a complete vitamin, since every single kind of common meat has zero Vitamin C. And it's deficient in other vitamins as well. So while plants aren't actually deficient in protein, meat is definitely deficient in vitamins. But I'm sure you never heard about vitamin deficiency in animal foods. All you've heard about is the supposed deficiency of protein in plants.

And speaking about biases, the whole protein-combining idea supposes that vegetarians are eating just one food, which is allegedly incomplete. Okay, how many people do you know who eat one food? And since nobody eats just one food, the whole idea of protein combining would be unnecessary anyway, even if it were true. So here again, what would be the point of harping on protein combining when it doesn't matter?

Using

some

common sense

Using

some

common sense

The largest land animals in the world, elephants, are exclusively vegetarian. They grow up to 10,000 pounds, by eating nothing but plant matter. They couldn't grow so big if plants weren't loaded with protein.

Amazingly, many readers have protested this by saying "But

we're not elephants!", as though they've made some sort of

point. If they mean to suggest that elephants don't need

protein, they're wrong: Every living creature on the planet

does. Elephants don't have some magical superpower which

allows them to live and grow without eating protein. They need

it, eat it, and use it, like everyone and everything else.

Perhaps the point was supposed to be that elephants utilize

protein differently? Not in any meaningful way.

All protein, whether plant or animal, is broken down into the

individual amino acids before the body uses it. And that goes

for any body, elephant, human, or otherwise.

Maybe the idea was that elephants get enough protein from plants

only because they eat so much? No, because once

you adjust for body weight, elephants eat less than we

do. Per 100 lbs. of body weight, Americans eat about 3 lbs. of

food per day, while elephants eat only 1.9. 23

And elephants aren't the only huge vegetarian animals roaming the planet. There are also horses, camels, giraffes, elk, rhinos, cattle, and more. Clearly if these massive animals are eating only plants, then plants have more than sufficient protein.

Ignoring common sense

We've seen what answers we get when we use credible resources and common sense. What happens if we just draw ridiculous conclusions?

I studied nutrition at the University of Texas at Austin, one of the largest universities in the country. They taught us that vegetarian or natural-foods diets were only for the stupid or naïve. I remember in particular one page from our textbook, which had three pie charts, each showing the proportion of macronutrients in vegetables, meat, and a human being, respectively. And by golly, the charts for the meat and for the human being were nearly identical! The implication was that meat is an ideal food, because it matches our body type so well.

It was at that point I realized I paid too much for my college education. Of course the charts were the same, because human beings are simply walking, talking meat. A body is a body, after all. By the logic presented in the textbook, if someone is white then they should eat white food.

And what about all the other animals? Elephants, giraffes, and horses would all have a pie chart that looks exactly like the one in the book. Shouldn't they be eating meat, too? Stupid elephants! If only they'd gone to college. You know, I really should go find a horse and try to get her to eat some meat. If she's not interested, I should show her the textbook so she can see that beef has the same makeup of her own body type. If that doesn't convince her, I should at least implore her to combine her proteins to make a complete protein.

Changing our vocabulary

Now that we know the truth about protein, it's time to start changing the way we talk about it. Here are some common ways in which the word protein is misused.

"Are beans a good source of protein?"

This question misses the point. When all whole foods

have plentiful protein, it's meaningless to talk about a "source" of

it. Food is a good source of protein. We don't

ask whether certain foods are good sources of calories, because all

foods have calories.

"I try not to eat a protein until lunchtime."

That's pretty much impossible, unless this person is not eating at

all, since all whole foods contain protein, and they

generally contain more than what you need.

There is no food that is "a protein". Foods contain

various nutrients, and protein is just one of them. It's

disparaging to food to identify it by just one of the nutrients it

contains. Would you call peanut butter a protein?

Because it's actually mostly fat, much more fat than protein.

Would you then call it a fat? Why so, since it has more

protein than you need? We have to stop equating foods with

individual nutrients. Foods contain nutrients, they

contain a collection of nutrients (not just one), and in any

event, all whole foods contain protein.

"Try to eat three servings of lean protein."

There is no such thing as "lean protein". There is only food, all of which contains protein.

We know that all food has protein, so something called "lean protein" should at least be low in fat, right? Think again. The National Institutes of Health says "lean protein" can have up to 3 grams of fat per 55 calories.24 That's up to 49% fat! Forty-nine percent is lean to these people?! Lean would be something like 10%. Half-fat would not.

So "lean protein" is wrong on two counts. First it assumes that only certain foods have protein, or that a food can be "a protein" (rather than being food), and second, "lean protein" isn't even lean.

Comparing infants' protein needs with adults'

Human breast milk is a mere 5.9% protein, when our protein

needs are highest, because we're growing faster than we ever will

again. We might therefore conclude that we'll need

less than 5.9% protein in adulthood. However, as The

Vegan RD points out, a comparison to babies on a

percentage-of-calories basis doesn't work, because babies consume

lots more calories than adults, relative to their body size. A

six-month old baby needs 37-49 calories per lb. of body weight per

day, which would be like a whopping 5600-7400 calories/day for a

150-lb. person. Adjusting for a baby's voracious appetite, a

baby's protein intake would look more like 13% of calories.*

So it's not right to conclude that we need less than 5.9% protein as

adults. But we could certainly conclude that we need less than

13% of calories as protein, and that's in fact what the official

sources say. Even so, common vegetables average more than 13%

protein, even after adjusting for bioavailability.

*NIH

says that a six-month-old weighs about 16.7 lbs. and needs 9.1g/d

of protein. That would be 85.6g/d for a 150-lb.

person. For a 2650 calorie/day diet, that would be (85.6 x

4) ÷ 2650 = 12.9% of calories as protein.

Related

- Dr.

McDougall on protein

- The Milk Letter: A message to my patients, by Robert M. Kradjian, M.D.

Note: Some footnote numbers have decimals because I inserted some new sources after the article was already written, and didn't want to have to painstakingly renumber all the notes.

1 The McDougall Plan, John A. McDougall, M.D., (1983) pp. 98-100

2 Diet for a New America, John Robbins, 1987, p. 172, citing the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition

3 Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids, Food and Drug Administration, Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 2005. (Protein Estimated Average Requirement and RDA for adults is 0.66 and 0.83g per kg of ideal body weight, respectively. These are married to the daily energy requirements listed in the same report for various genders, ages, heights, weights, and activity levels, to get the range of percentage of calories from protein.)

4 Protein and Amino Acid Requirements in Human Nutrition (PDF), World Health Organization (2007). Recommendations on pp. 125-126: an "average requirement" of 0.66 g of protein per kg of body weight, and a "safe level" of 0.86 g/kg. Bell curve showing protein requirement by population on p. 39, section 3.2.4.

5 USDA FoodData Central database (accessed August to December 2009). I took the average of these foods for each group:

FRUIT: Average of Apples, Pears, Grapes, Bananas, Plums, Oranges, Grapefruit, Watermelon, Strawberries, Peaches, Nectarines, Cantaloupe.

VEGETABLES: Average of Broccoli 27.2%, Carrots 8.7%, Celery 17.3%, Corn 13.4%, Cucumber 17.3%, Green Beans 21.6%, Lettuce icberg 25.7%, Mushrooms white 31%, Onions 12.4%, Peas 28.8%, Potato 10.8%, Spinach 49.7%, Tomato 19.6% (accessed December 2009)

To get the percentage of protein, I multiplied the protein grams by four (as per Report on the Working Group on Obesity, Appendix B, US Food & Drug Administration website), then divided by the total number of calories.

6-8 (Removed from article)

9 Shattering the Protein Myth, Debra Blake Weisenthal, Vegetarian Times (March 1995)

10 Vegetarianism: Movement or Moment?, Donna Maurer (2002), p. 37

11 The McDougall Plan, p. 101

12 Diet for a New America, p. 175

13 World Health Organization, p. 135

14 The McDougall Plan, p. 97

15 Vegetable Proteins Can Stand Alone, Dennis Gordon, M.Ed,R.D., Journal of the American Dietetic Association (March 1996, Volume 96, Issue 3), pp. 230-231

16 Vegetarianism: Movement or Moment?, p. 38.

17 Complementary Protein Myth Won't Go Away!, Jeff Novick, M.S., R.D., Healthy Times (May 2003)

18 Vegetarians: Pondering Protein?, Andrew Weil, M.D., DrWeil.com (Dec. 11, 2002)

19 "Complete" Proteins?, Charles R. Attwood, M.D., F.A.A.P., VegSource.com (accessed Sep. 4, 2009)

20 Diet for a Small Planet, 10th Anniversary Ed., Frances Moore-Lappé (1982), p. 162

21 The Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS), Gertjan Schaafsma, Journal of Nutrition, 2000; 130:1865S-1867S

22 Protein Overload, John A. McDougall, M.D., The McDougall Newsletter (January 2004)

23 For elephants, Smithsonian National Zoological Park. For people, average weight was calculated by comparing U.S. population by age from the Center for Disease Control with U.S. weight by age from the U.S. Census, and then compared with food intake as per the USDA Agriculture Fact Book 2001-2002.

24 National Institutes of Health website (accessed August 5, 2009)

25 Dietary protein adequacy and lower body versus whole body resistance training in older humans, Wayne W Campbell et al., J Physiol. 2002 July 15; 542(Pt 2): 631-642. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.020685

26 Influence of protein intake and training status on nitrogen balance and lean body mass. Tarnopolsky MA, MacDougall JD, Atkinson SA. J Appl Physiol. 1988 Jan;64(1):187-93.

27 Protein requirements and muscle mass/strength changes during intensive training in novice bodybuilders. Lemon PW, Tarnopolsky MA, MacDougall JD, Atkinson SA. J Appl Physiol. 1992 Aug;73(2):767-75

28 Nutrition

and

Athletic Performance, joint position of the American Dietetic

Association, Dietitians of Canada and the American College of Sports

Medicine (March 2009)

29 Effects

of

protein and amino acid supplementation on athletic performance,

Kreider RB, Sportscience 3(1), 1999

30 Vegan

Weightlifting:

What does the science say?, Jack Norris, RD, Vegetarian

Journal (2003, Issue 4)

31 Human

Energy Requirements, Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert

Consultation, Chapters 2 & 4, October 2001

32 Effects

of slow versus fast-digested protein supplementation combined with

mixed power training on muscle function and functional capacities

in older men, M C Dulac et al, British Journal of Nutrition

(2020 Jun 5)

33 If you wondered why both figures aren't 20%, it

depends on which direction you're looking towards. For

example, if two items cost $80 and $100, then the $80 item costs 20%

less than the $100 item (20÷100), but the $100 item costs 25% more

than the $80 item (20÷80). For the example in which someone

reduces calories by 20% but needs 25% more protein as a percentage

of calories: 2500 kcal > 2000 kcal (20% fewer calories) • 8%

protein of 2500 kcal = 200 kcal • 200 kcal ÷ 2000 kcal = 10% •

10%÷8% = 25%.

34 Plant

Foods Have a Complete Amino Acid Composition,John McDougal,

M.D., Circulation, 25 un 2002

While I didn't cite this in the article, in How

Much Protein is Needed? (PDF), Professor T. Colin Campbell

agrees (p. 18) that looking at the percentage of calories from

protein is preferable to looking at the number of grams, because

grams will be different for different genders while percentages will

be the same. He also shows that the U.S. government

recommendation for protein intake works out to about 9% of calories.